As an Arab woman, my whole life I heard the term ‘modesty’ as a sports term. I remember sitting in on conversations with family friends and relatives, who described how they trained their daughters for ‘modesty’. This training involved many different approaches. When some daughters became teenagers, they were no longer allowed to leave the house in skirts above the knee or tops exposing her shoulders. Others would be made to wear the hijab altogether, with little consideration to their choice. The people who perplexed me the most were those who spoke of ‘training’ for modesty beginning at early childhood. I have unfortunately come across too many who ‘trained’ their daughters, sometimes as young as five years old, to be wearing t shirts in swimming pools or leggings under their dresses, all in the name of getting them ‘used to’ modesty.

Their argument claims that forcing young girls into ‘modest’ dressing ensures that when they grow up they replicate the same style. In many situations where I listen along to these kinds of conversations, I feel as if rigorous piano training or something of equal nature is being discussed and not…putting on clothes.

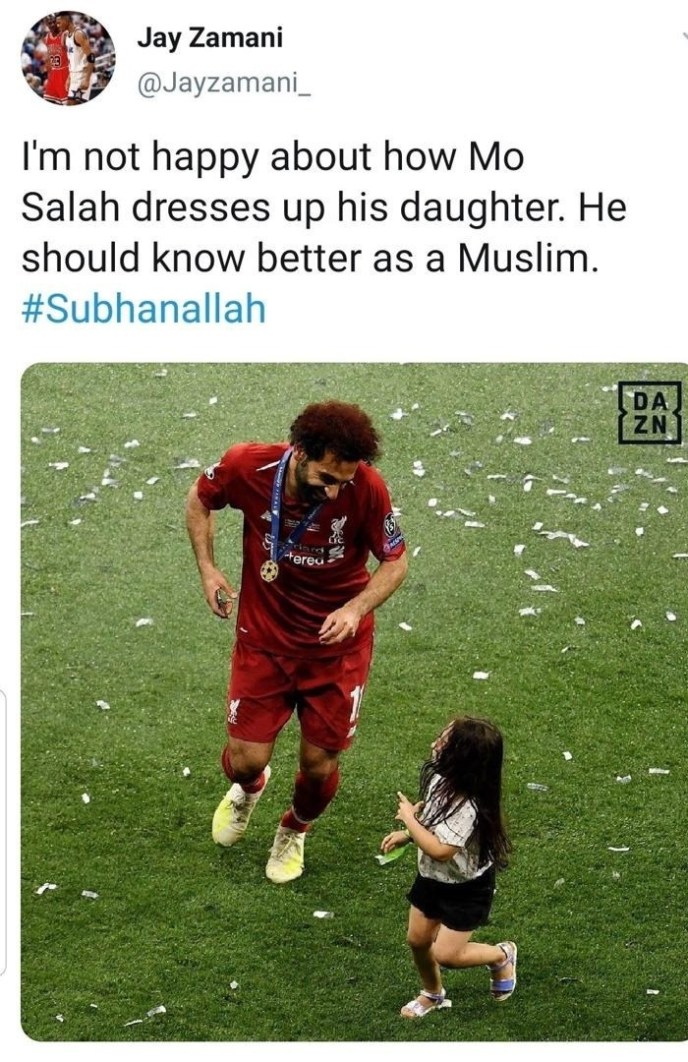

Scrolling through Twitter recently reminded me of this phenomena. A user tweeted something that took my breath away, which is saying a lot considering the cesspool that Twitter can be most of the time. It was that bad.

The tweet reads; “I’m not happy about how Mo Salah dresses up his daughter. He should know better as a Muslim.”

In the photo is a joyous Mohamad Salah, the famous Liverpool soccer player who has become the Egyptian sweetheart of the world, with his young daughter Mecca. Mecca is in black shorts and a t shirt. Her hair flies around her face as she chases a soccer ball alongside her father.

While one could easily dismiss this as usual nonsense that is posted on Twitter by men who think their misogyny is edgy and funny, I found myself extremely disturbed and reliving a lot of conversations while reading the replies of agreement to the initial tweet. Every conversation about ‘decency’ and how men only want to marry women who ‘dress decently’. Every ‘women are like lollipops’ conversation. One user tweeted back that “decency needs to be taught at a young age”.

I found myself disturbed because this sexualization of children and control of their bodies in the name of ‘training’ for later life modesty is a real phenomena. Many people argue that it is not an especially big deal if parents make the decision for their young daughters to dress in a conservative way because it is the same as a parent ‘forcing’ their daughter to dress in ‘liberal’ clothing. I use all these terms loosely because I am unsure what any of them mean. I don’t know how children’s clothing can be liberal or conservative. Children should just be dressed and treated as children, not as bearers of cultural norms and modesty.

Following that especially horrid tweet which made the rounds online, I came to the horrific realization at how strong the privilege of Arab men is. Now don’t get me wrong. I love Mo Salah. I think he is doing a great job representing Arabs in the diaspora and Muslims as well.

But following the posting of the photo of Salah and his young daughter came a stream of posts from the soccer heart throb in um…some very scantily clad clothing choices. Salah is on vacation in these photos, smiling wide and giving fans a great view of some his ‘assets’ that we aren’t used to seeing on the field.

Now again, don’t get me wrong. I liked and favorited this eye candy vivaciously and sent them to all my girl group chats. But reading the comments on these photos and contrasting them to the photos of Salah and his young daughter showed a stark contrast in how Arab society views the bodies of men and women.

Salah is allowed to be as at liberty with his body as he wants. Beneath his shirtless photos are a plethora of Quranic quotes praying for his protection and the adoration of men and women alike. In the photos of his young daughter is scorn that she is going to ‘get used to’ showing her legs in shorts. And I dare make the comparison to Egyptian actress Rania Youssef, who last year was forced to apologize to the entire country of Egypt and the greater Arab world for wearing a sheer dress that exposed most of her legs and allegedly some more.

The double standards here are so clear that I don’t know if I will ever be able to look at a photo of barely clad Salah again. While I also adore him, the leniency he is afforded serves as a reminder that men can own their bodies and do with them what they please and still be regarded as ‘fakhr al arab’ or the pride of the Arabs, while no matter how much Arab women succeed and represent our communities in arts, film, music, science and politics, the question will always boil down to if she is dressing her body in a way that society deems as respectable.

My aim isn’t to debate the merit of hadiths discussing menstruation, nor to interrogate Islam’s feminism based on such discussions. The point I’d like to make is that conversations about menstruation are complex, however, the fact that we often view Islam through a male-tilted lens often takes questionable hadiths about menstruation (i.e. women cannot hold the Quran) and compounds them into more dramatic cultural practices. Historically, women haven’t been allowed to become Islamic leaders because, as my religious tutor used to say, a female imam could not guide prayer for a week and everyone would know why, bringing her shame. However, Myriam Francois argues in a

My aim isn’t to debate the merit of hadiths discussing menstruation, nor to interrogate Islam’s feminism based on such discussions. The point I’d like to make is that conversations about menstruation are complex, however, the fact that we often view Islam through a male-tilted lens often takes questionable hadiths about menstruation (i.e. women cannot hold the Quran) and compounds them into more dramatic cultural practices. Historically, women haven’t been allowed to become Islamic leaders because, as my religious tutor used to say, a female imam could not guide prayer for a week and everyone would know why, bringing her shame. However, Myriam Francois argues in a

On the subject of forks, why should we Arabs need forks when we have so many finger-licken-good foods? You have no problem digging into some chocolate flavored hummus with pretzels from Whole Foods, can you fault us for doing the same? Bread, I find (as well as most of the world, in fact) is a great vehicle for meals. You should try dipping things in bread sometimes, Tucker, I think you’ll find your palate much enhanced.

On the subject of forks, why should we Arabs need forks when we have so many finger-licken-good foods? You have no problem digging into some chocolate flavored hummus with pretzels from Whole Foods, can you fault us for doing the same? Bread, I find (as well as most of the world, in fact) is a great vehicle for meals. You should try dipping things in bread sometimes, Tucker, I think you’ll find your palate much enhanced.  Carlson made these particular racist comments a decade ago, but just last week

Carlson made these particular racist comments a decade ago, but just last week

Sometimes I imagine what it would be like praying on a white marble floor in the center of a great mosque. There’s no roof, only a blue sky and the looming shadow of the minarets. The image comes, perhaps, from my early memories walking through the Ummayad Mosque with my family, where the hustle and noise of the Hamideyyah Souq faded to a hum and the cooing of pigeons. I imagine what the smooth stone would feel like on my palms and forehead. The smell and feel of a cool breeze. In the Alhambra in Spain, architects incorporated water into their gardens and marble courtyards, as though, even in a lush landscape, the Muslims there remembered our religion’s birth in a dry desert and celebrated the blessing of clean water. For that reason, I might put a fountain in my mosque, like the Andalusian Muslims did, even as I keep the striped, Syrian arches. In a mosque like that, I think, I’d find spirituality.

Sometimes I imagine what it would be like praying on a white marble floor in the center of a great mosque. There’s no roof, only a blue sky and the looming shadow of the minarets. The image comes, perhaps, from my early memories walking through the Ummayad Mosque with my family, where the hustle and noise of the Hamideyyah Souq faded to a hum and the cooing of pigeons. I imagine what the smooth stone would feel like on my palms and forehead. The smell and feel of a cool breeze. In the Alhambra in Spain, architects incorporated water into their gardens and marble courtyards, as though, even in a lush landscape, the Muslims there remembered our religion’s birth in a dry desert and celebrated the blessing of clean water. For that reason, I might put a fountain in my mosque, like the Andalusian Muslims did, even as I keep the striped, Syrian arches. In a mosque like that, I think, I’d find spirituality.

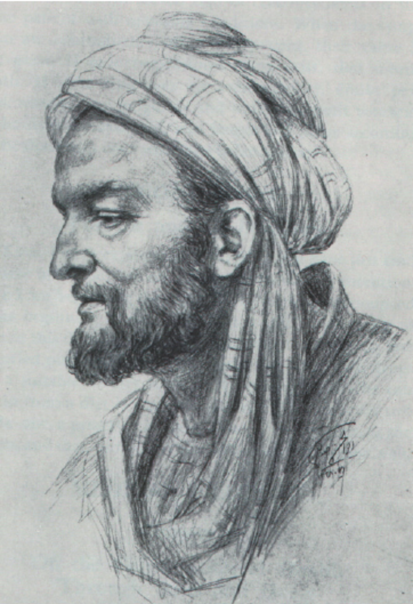

After all, in his autobiography, Ibn Sina writes that whenever he suffered from writer’s block or grew frustrated with a text he could not understand, he would go to the mosque and pray, then return home and drink half a glass of wine.

After all, in his autobiography, Ibn Sina writes that whenever he suffered from writer’s block or grew frustrated with a text he could not understand, he would go to the mosque and pray, then return home and drink half a glass of wine.